Text and illustrations

by Judith P. Raynault

by Judith P. Raynault

We don’t know how Quebec’s First Nations discovered that maple water tasted good. This sap, which appears in the spring thaw when nights freeze the ground and days warm it up, is available only for a short window of time. What chance accident lead them to discover it?

We can speculate. Maybe a hunter’s weapon got stuck in the trunk, and when he went to retrieve it water began to pour. Or a tree with a broken branch accumulated in its wound a sap icicle and a kid then discovered this natural Mr Freeze.

However it happened, this fortuitous moment lead the indigenous people to collect maple water every year in bark or terracotta receptacles, and to put hot rocks into it to thicken the water and make it sweeter. As well as tasting good, they thought it had energising properties (although, in retrospect, they were probably just on a sugar high). They also used it as an eye lubricant, to clear them from the smoke trapped in the long houses.

We don’t know what they thought of the white men when they first arrived. We can only assume they didn’t know these newcomers would soon either kill them or put them on reserves and forget about them for a very long time. If they had, they probably would not have taught the settlers how to survive the Quebecois winter.

We can speculate. Maybe a hunter’s weapon got stuck in the trunk, and when he went to retrieve it water began to pour. Or a tree with a broken branch accumulated in its wound a sap icicle and a kid then discovered this natural Mr Freeze.

However it happened, this fortuitous moment lead the indigenous people to collect maple water every year in bark or terracotta receptacles, and to put hot rocks into it to thicken the water and make it sweeter. As well as tasting good, they thought it had energising properties (although, in retrospect, they were probably just on a sugar high). They also used it as an eye lubricant, to clear them from the smoke trapped in the long houses.

We don’t know what they thought of the white men when they first arrived. We can only assume they didn’t know these newcomers would soon either kill them or put them on reserves and forget about them for a very long time. If they had, they probably would not have taught the settlers how to survive the Quebecois winter.

But this was only the beginning of colonisation, when France was sending out people only for fur trading. There was still some exchange (material and intellectual) with the indigenous people. In the case of maple, the exchange went as follows: one people showed how to harvest the sap, the other brought their metal tools and iron and copper cauldrons to collect it. And because the history of the Western world has an unfortunate habit of focusing on the white man, here is where the story of the sugar bush passes from the hands of the First Nations to those of the French-Canadians.

Over the years, the latter refined the art of tapping trees and increased production. The preservation techniques were not advanced enough to make maple syrup in big quantities, but the settlers transformed the maple sap into what was called “country’s sugar”, or “red sugar”. Some serfs even paid their rent to the lord in sugar. Exported to France, it never gained in popularity because it couldn’t be whitened—white being a sign of purity (typical).

Over the years, the latter refined the art of tapping trees and increased production. The preservation techniques were not advanced enough to make maple syrup in big quantities, but the settlers transformed the maple sap into what was called “country’s sugar”, or “red sugar”. Some serfs even paid their rent to the lord in sugar. Exported to France, it never gained in popularity because it couldn’t be whitened—white being a sign of purity (typical).

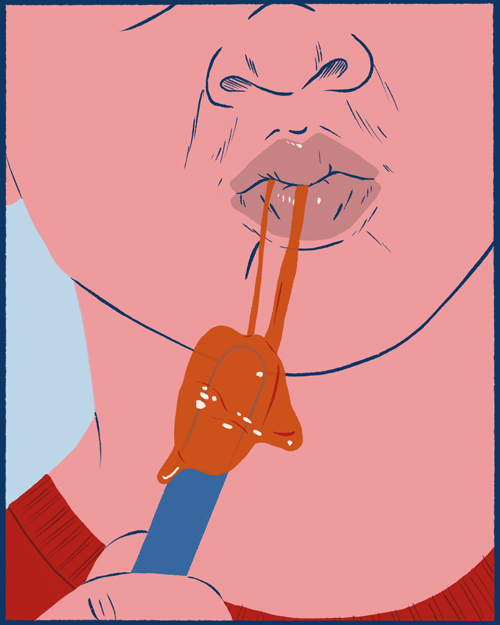

Maple taffy is a sugar candy made by boiling maple syrup for a longer time, but not long enough for it to crystallise and become sugar.

Maple taffy is a sugar candy made by boiling maple syrup for a longer time, but not long enough for it to crystallise and become sugar.

For a long time the shack remained a mere shelter made of planks or bark, erected and demolished each spring, under which were placed the cauldrons to boil the maple water. The permanent small wooden cabin appeared around 1820; a closed hut allowing for less heat to be lost during sugar production. Although the custom of meeting there with family and friends to socialise, eat, and flirt existed at least a century before, it now had an official name: the sugar party.

Twenty years later the Catholic Church is law in Quebec. Between 1840 and 1960, the sugar shack was considered a social plague by some bishops. The meal consisting of baked beans, ham, omelet, pork scratchings and syrup, was frowned upon by the clergy during this time of Lent and fasting. The sugar parties were therefore often supervised, with prayers and “shack blessings”. And we can only assume the priest in attendance had a cheeky copious meal too.

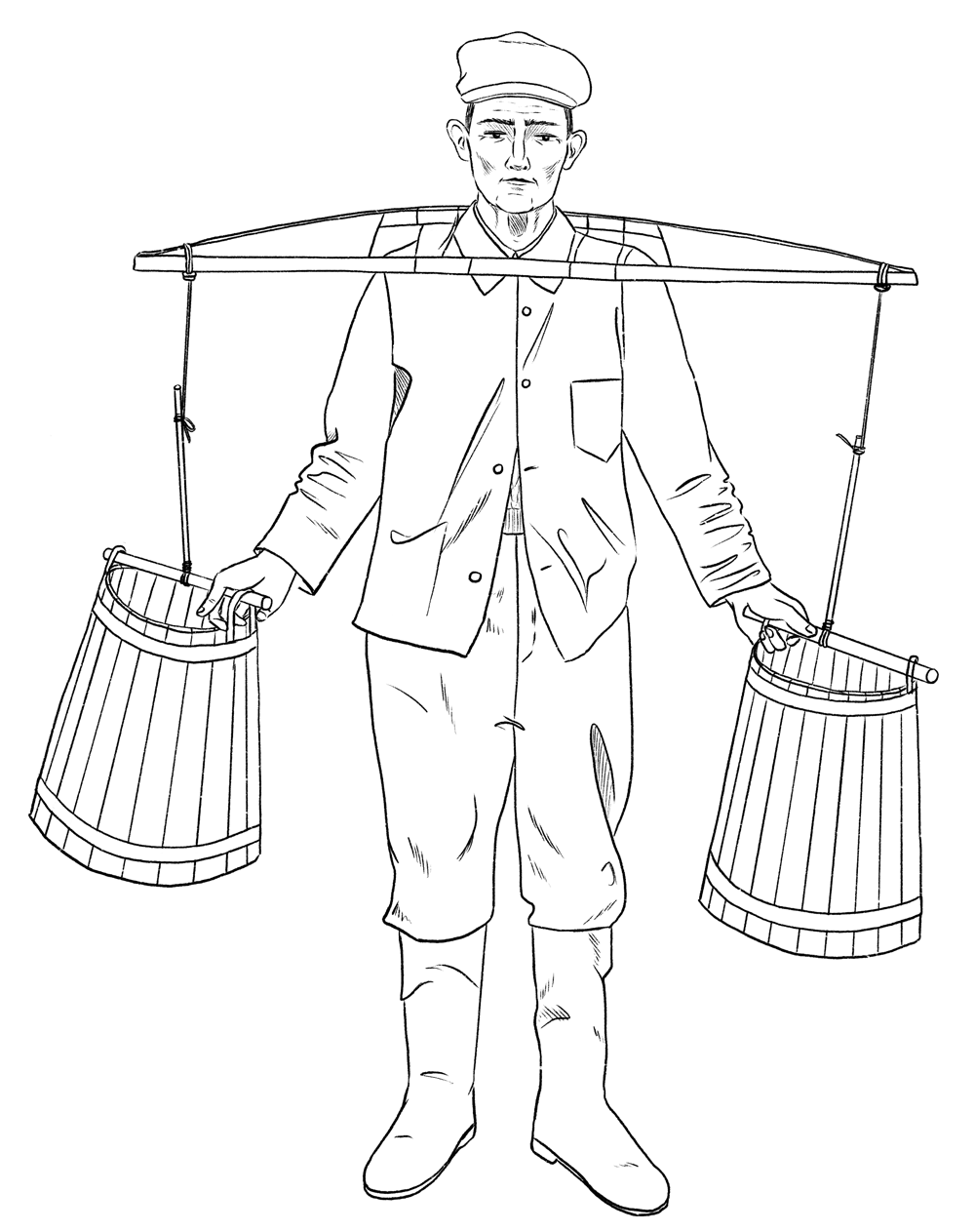

For farmers, this time of spring when the soil is still too frozen to be cultivated allowed them to look after the shack. It became the nerve centre of the family activity. Even the dog helped by pulling the sledge filled with empty buckets through the sugar bush during tapping. And a horse or ox was used to bring back barrels filled with sap.

Twenty years later the Catholic Church is law in Quebec. Between 1840 and 1960, the sugar shack was considered a social plague by some bishops. The meal consisting of baked beans, ham, omelet, pork scratchings and syrup, was frowned upon by the clergy during this time of Lent and fasting. The sugar parties were therefore often supervised, with prayers and “shack blessings”. And we can only assume the priest in attendance had a cheeky copious meal too.

For farmers, this time of spring when the soil is still too frozen to be cultivated allowed them to look after the shack. It became the nerve centre of the family activity. Even the dog helped by pulling the sledge filled with empty buckets through the sugar bush during tapping. And a horse or ox was used to bring back barrels filled with sap.

After boiling the maple sap, the sugar produced was poured into moulds before it hardened. These homemade moulds made of wood took on different shapes, such as hearts or roosters—the kind of object that is boring to look at in a museum but becomes suddenly interesting when seen in action.

For nearly three centuries, the country’s sugar was the only product derived from maple trees in large quantities. The syrup and taffy were eaten on the spot at the cabin. It was only around 1920-1930 with the arrival of the metal barrel, then the tin can, that syrup could be preserved and distributed on a large scale. By the 1950s and 1960s, the production of maple syrup was supplanting that of sugar.

From the indigenous people’s birch receptacles to the tubing that appeared in the late 1960s, by way of buckets transported by humans then by animal power, maple tree harvesting has evolved considerably. Today Quebec supplies 70% of all maple products on the planet.

It is now a tradition well ingrained in the life of the Quebecois. With lower numbers of familial sugar shacks, the commercial shack is ultra (some would say much too) popular. A custom that brings together family and friends to welcome the new season while working ondeveloping type 2 diabetes enjoying aaaall the sugar.

For nearly three centuries, the country’s sugar was the only product derived from maple trees in large quantities. The syrup and taffy were eaten on the spot at the cabin. It was only around 1920-1930 with the arrival of the metal barrel, then the tin can, that syrup could be preserved and distributed on a large scale. By the 1950s and 1960s, the production of maple syrup was supplanting that of sugar.

From the indigenous people’s birch receptacles to the tubing that appeared in the late 1960s, by way of buckets transported by humans then by animal power, maple tree harvesting has evolved considerably. Today Quebec supplies 70% of all maple products on the planet.

It is now a tradition well ingrained in the life of the Quebecois. With lower numbers of familial sugar shacks, the commercial shack is ultra (some would say much too) popular. A custom that brings together family and friends to welcome the new season while working on

The laughter.

The family.

My father’s parents, his nine brothers and sisters and their spouses, children and now grandchildren. After Christmas and New Year’s, the day at the sugar shack is the third-biggest family party of the year. The festivity celebrating the arrival of spring.

The dirt road leading to the sugar bush. The fear of jamming the car in a mud hole. The puzzle, once at the shack, to park between cars and trees while making sure you can get out at the end of the day.

The ‘réduit’1 too sweet for my taste, even after adding a dram of Beefeater like some of my aunts do.

The outside picnic tables around which we crowd like at the commercial shacks, but where we take the time to eat, drink, talk, argue, and especially laugh.

The maple syrup. On pancakes yes, but also on ham, eggs, bacon, baked beans, sausages. It’s almost like pouring it into your mouth.

The very long queue for the delicious pancakes cooked by grandma then, by cousin now. The people trying to chat and cut. Others pretending they’re getting the extra one “for mum”. The year when an aunt, sacrilege, made “healthy” pancakes that were not 90% constituted of deep fried fat.

The uncles and aunts who take turn washing the dishes after the meal. Always the same ones offering to help.

The family.

My father’s parents, his nine brothers and sisters and their spouses, children and now grandchildren. After Christmas and New Year’s, the day at the sugar shack is the third-biggest family party of the year. The festivity celebrating the arrival of spring.

The dirt road leading to the sugar bush. The fear of jamming the car in a mud hole. The puzzle, once at the shack, to park between cars and trees while making sure you can get out at the end of the day.

The ‘réduit’1 too sweet for my taste, even after adding a dram of Beefeater like some of my aunts do.

The outside picnic tables around which we crowd like at the commercial shacks, but where we take the time to eat, drink, talk, argue, and especially laugh.

The maple syrup. On pancakes yes, but also on ham, eggs, bacon, baked beans, sausages. It’s almost like pouring it into your mouth.

The very long queue for the delicious pancakes cooked by grandma then, by cousin now. The people trying to chat and cut. Others pretending they’re getting the extra one “for mum”. The year when an aunt, sacrilege, made “healthy” pancakes that were not 90% constituted of deep fried fat.

The uncles and aunts who take turn washing the dishes after the meal. Always the same ones offering to help.

The few metal buckets hanging under the pipe to look more “authentic”. The blue tubes that run everywhere in the woods, and the children running with them. Children playing, laughing ... crying.

The year when two cousins, sisters—one called “the artist” because rumour had it she was a stripper in Ontario—got into a biting and hair-pulling fight. The family standing there, bewildered. Then an aunt exclaiming “What the hell?!” followed by the separation of the squabblers by the boyfriend of one of them. The countless years of retelling this story with joy.

The cauldron in which the syrup boils in order to turn it into taffy, as we collectively dip our wooden spatulas in while exchanging microbes and opinions to determine “Is it ready?” The question being: is it thick enough to be poured onto the snow?

The sun of a nascent spring that warms heads finally free from toques (beanies). The sun melting the snow but leaving us enough to lay the taffy.

The taffy, this amber substance situated somewhere between solid and liquid, which brings joy to young and old alike. Ultimate dessert of this already sweet meal, it announces the imminent end of the day. The kids—whose sticky hands you better avoid—have to leave before crashing from their sugar high. As do the parents.

The family.

The laughter.

The year when two cousins, sisters—one called “the artist” because rumour had it she was a stripper in Ontario—got into a biting and hair-pulling fight. The family standing there, bewildered. Then an aunt exclaiming “What the hell?!” followed by the separation of the squabblers by the boyfriend of one of them. The countless years of retelling this story with joy.

The cauldron in which the syrup boils in order to turn it into taffy, as we collectively dip our wooden spatulas in while exchanging microbes and opinions to determine “Is it ready?” The question being: is it thick enough to be poured onto the snow?

The sun of a nascent spring that warms heads finally free from toques (beanies). The sun melting the snow but leaving us enough to lay the taffy.

The taffy, this amber substance situated somewhere between solid and liquid, which brings joy to young and old alike. Ultimate dessert of this already sweet meal, it announces the imminent end of the day. The kids—whose sticky hands you better avoid—have to leave before crashing from their sugar high. As do the parents.

The family.

The laughter.

1. Thickened maple water.

The Sugarshack, 2014

Acrylic screen printed on cotton

Acrylic screen printed on cotton

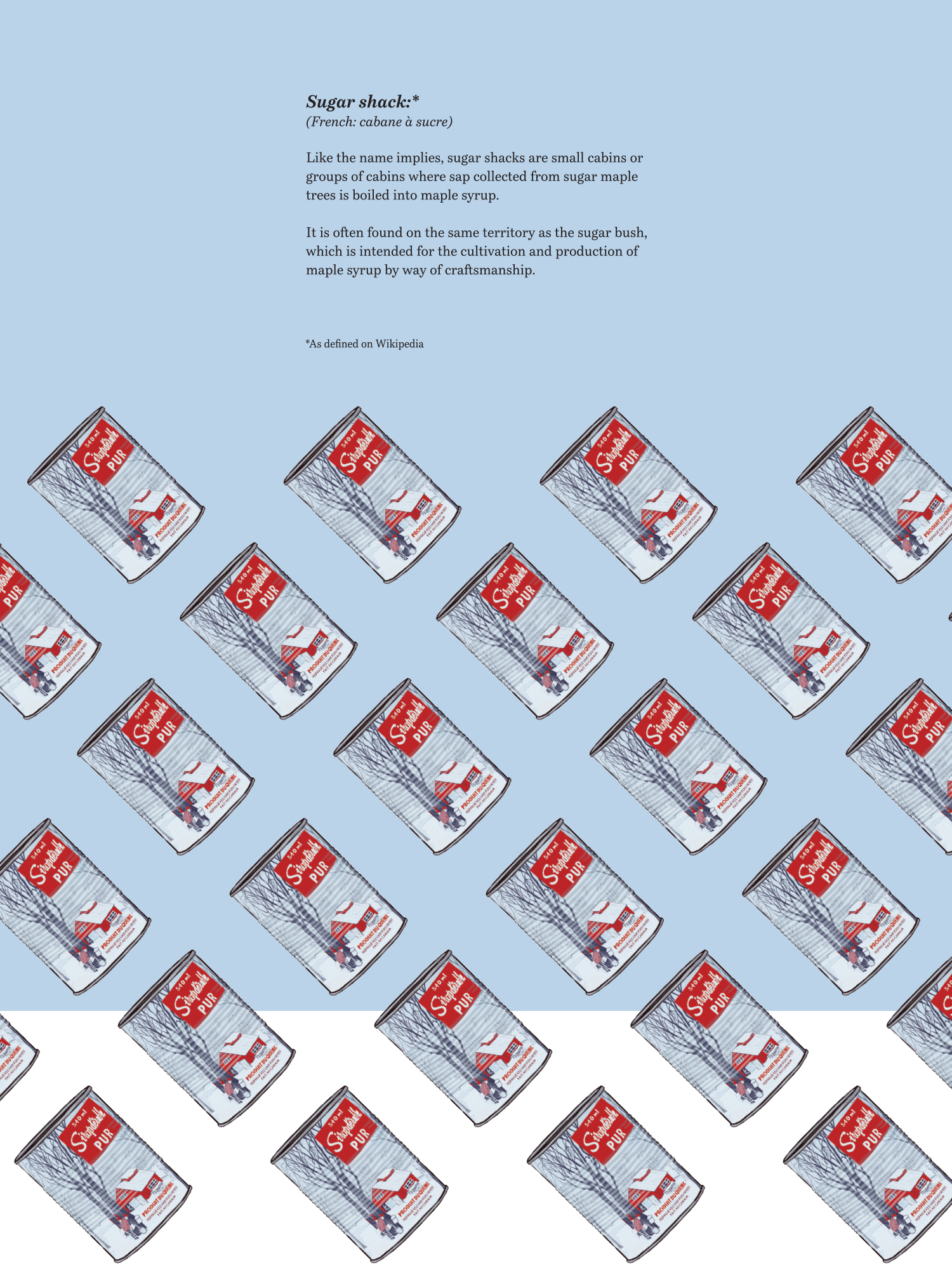

This classic tin design was born out of a contest organised by the Ministry of Agriculture of Quebec in 1951, and the name of the winner is unfortunately unknown. Although some people consider its look dated and would like to see it changed, there’s no denying that the illustration has been around for so long that it is now iconic. It both tells the maple syrup story and is part of it.

Interestingly, before the introduction of the tin can maple syrup was sold in various glass containers, something that has come back as a trend in recent years with more contemporary designs.

Credit where credit is due

Editor-in-chief

Judith P. Raynault

Contributing editor

John Lynn

Art director and Designer

Judith P. Raynault

(I combined titles because we’ll all get tired of reading my name by the end of this page)

Cover

Judith P. Raynault, with the help of Katie Jane Murray

Contributors (thank you!!)

Jason Cantoro & Léonie Flower

© 2018 Judith Poitras-Raynault

All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is strictly prohibited.

Contact

judithraynault@gmail.com

Special mention

The 1941 short documentary Maple Sugar Time from Library and Archives Canada

was the basis for the comics on pages 8 and 10.

Source: Library and Archives Canada. Metropolitan Toronto

Library Board fonds, 1987-0337. IDC: 52208.